Foster equity, strengthen engagement, and build visual literacy with Artstor on JSTOR virtual field trips

Francis William Edmonds. The New Bonnet. 1858. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Remember how fun field trips were as a kid? Stepping out of the classroom and into another world, demonstrating how what we learn in school manifests in the “real” world? Well, who ever said field trips were just for kids, or that you had to step out of the classroom to experience one?

Using Artstor’s collections and JSTOR’s unique tools, you can take your students on countless field trips with little more than a laptop to access the vast digital archives available on Artstor on JSTOR. What’s more, you can use these “virtual field trips” as a way to foster equity in the classroom while ensuring students learn core lessons and broadly applicable visual and digital literacy skills.

Take it from me. I’ve used Artstor and JSTOR virtual field trips in my own college courses to switch up the classroom dynamic, learn in new ways, and have fun with complex course material. Read on to see how you can do the same.

First off, what is a virtual field trip?

A virtual field trip is a guided learning exercise that pairs a digital archive—such as Artstor on JSTOR—with a set of tasks that prompt students to engage with and respond to what they are seeing, reading, hearing, and experiencing.

What should a virtual field trip prompt look like?

While there is always room for flexibility, generally speaking, your prompt should:

- Identify which digital archive you want students to use. You can choose based on your course theme or lecture topic.

- Provide directions to students on how to use the archive. Artstor on JSTOR has directions and FAQs for new users that you can use to guide and direct students.

- Include questions that students can respond to individually, in small groups, together with the whole class, or—ideally—a combination of all three.

See the bottom of this post for a sample virtual field trip prompt

How can a virtual field trip promote positive learning outcomes?

Virtual field trips provide students with widely applicable research and critical thinking skills, but they also help students gain specific skills in visual and digital literacy, which may be new to some.

Visual literacy is the ability to interpret, probe meanings, and gain information about the image being viewed. Practicing visual literacy sparks intellectual curiosity and develops critical thinking and analytical skills. Students frequently interact with images on social media, but rarely practice viewing a single image and spending time making observations and drawing meaning from it to better understand the world around them. Of course, students don’t need to enroll in an art class to exercise visual literacy. As Virginia Seymour explored extensively in her Learning to Look column on JSTOR Daily, there are creative ways to engage with visual literacy in every discipline. Seymour even provides a range of lesson plans to help students cultivate visual literacy. These plans also include hands-on guides to support students in their image-based projects.

Digital literacy encompasses “the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills” (American Library Association 2011). While it’s easy to turn to Google Images, such open source content is often altered from the original, leading to potential copyright issues. These sources make it difficult for users to determine authenticity and quality. Introducing students to digital archives helps them access verified information and reliable, authentic images for academic purposes. When they are exposed to verifiable images, they are better able to distinguish them from Google Images.

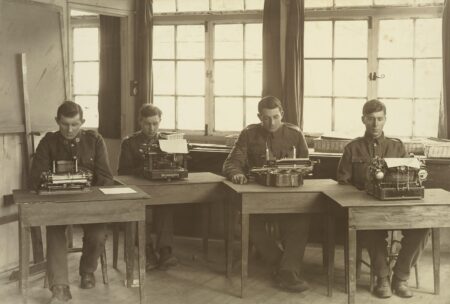

- Alan McMillan and three unidentified WWI soldiers seated at typewriters at Oatlands Park, Surrey, England. 1918. Museum of New Zealand – Te Papa Tongarewa.

- Gameboard and Gaming Pieces. ca. 1550–1295 B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

How can virtual field trips foster equity, boost engagement, and promote information literacy in the classroom?

Virtual field trips to foster equity

There are obstacles to planning field trips that affect faculty and students. With virtual field trips, there’s no need to resolve the cost, time, and transportation logistics involved with an actual field trip, especially for faculty with heavy course loads or research obligations, students with significant extracurricular obligations or personal limitations, and/or institutions with insufficient resources. These obstacles are removed and accessibility is ensured when students are directed to digital archives they have access to through their institutions.

Moreover, as Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) becomes an increasingly important topic in education, instructors must reflect on the accessibility and fairness of their assignments and projects for all students in their classes, including those assigned without issue in previous years.

Virtual field trips to boost student engagement

A recent study analyzing Gen Z learning habits found that roughly 90% of its respondents reported they learn best by either doing or seeing. The same study found that Gen Z students increasingly want their education to feel relevant and practical. Combining these findings with recent declarations by subject matter experts who have identified a student engagement crisis, it is clear that it has never been more important for educators to meet the needs of current and future generations of students.

Luckily, educators can increase student engagement by tapping into existing technologies—including image-based databases like Artstor on JSTOR—to help students learn relevant and practical lessons by doing and seeing.

In my own teaching, virtual field trips have been a great way to engage students, nearly all of whom are Gen Z digital natives. By steering my students toward image-based databases in the form of a structured activity with opportunities for self-, peer-, and instructor-led teaching, I helped students learn by seeing, doing, and engaging with visually immersive material. Further, in course evaluations and periodic feedback surveys, students noted that virtual field trips provide them with practical skills and experiences that are relevant to their broader education.

Educators can offer the same sets of readings and clips for students for class discussion purposes, but there is great value in allowing students to explore a topic of personal interest. Doing so gives them the opportunity to engage deeply with images or other media of their own choosing. They are more likely to engage in a dive deep into a topic that resonates with them. If they are naturally curious about an image, they will connect with it, practice translating the visual information in their own words, and be able to speak intelligently about it in a class discussion or assignment.

Virtual field trips to promote digital literacy

It’s essential that educators foster digital literacy, which helps students distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate databases and resources. This is important for helping students complete assignments and papers, while also cultivating their intellectual growth and critical thinking skills. While open access content can be helpful for students, not all students can distinguish a peer-reviewed journal article from a non-reviewed blog post. While we cannot prevent students from using Google as a go-to information hub, we can provide them with a “toolkit” for recognizing quality.

Virtual field trips that utilize databases like Artstor on JSTOR can be an integral part of this toolkit. It provides students with a reliable repository of quality images that are rights-cleared for use and contextualized using evidence-based information. Renowned museums, galleries, and other cultural organizations furnish that well-researched information. . By showing students what a reputable database and search engine looks like, and teaching them how to locate and operate such a database, students will gain invaluable digital literacy skills.

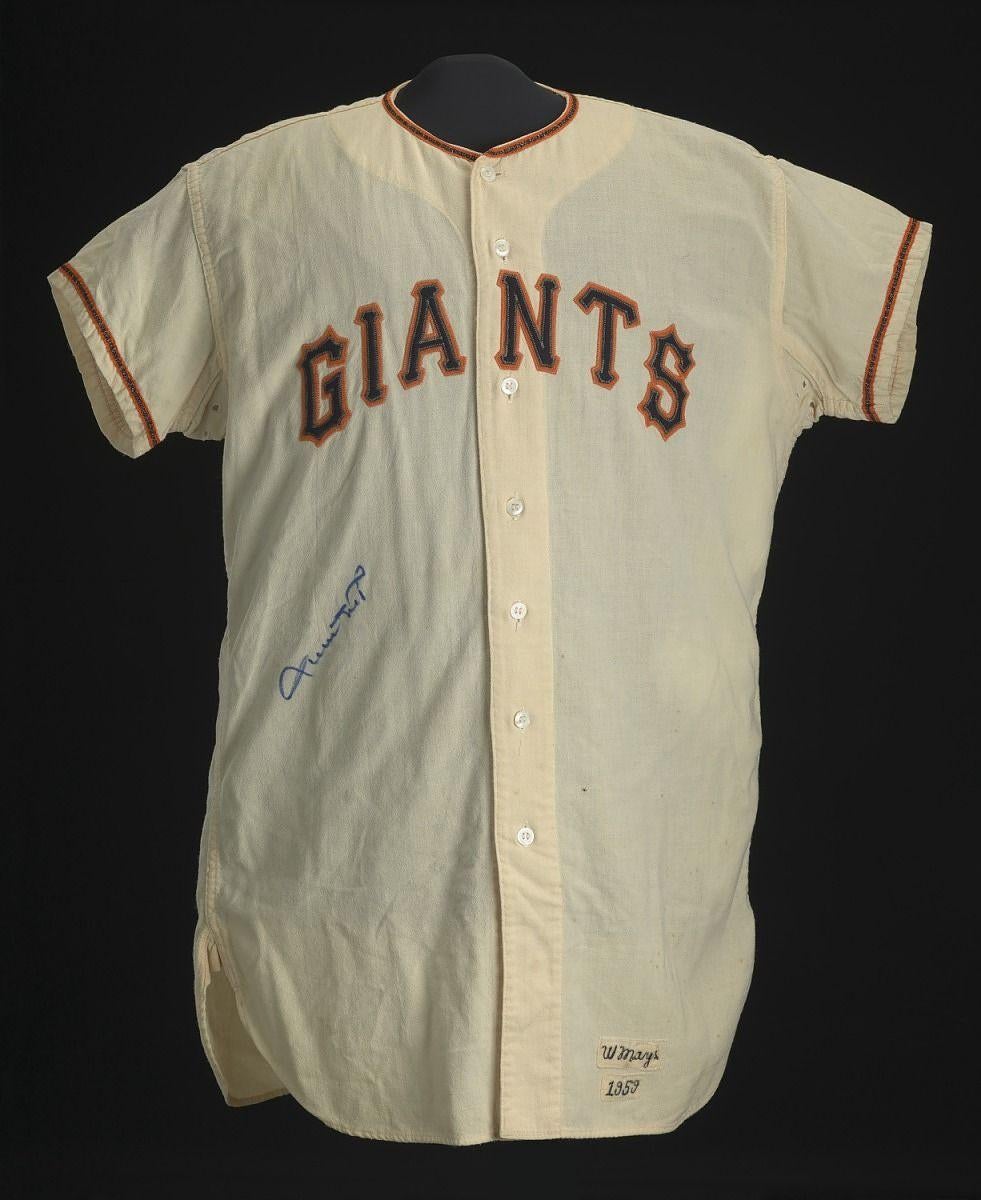

San Francisco Giants spring training jersey worn and signed by Willie Mays. 1959. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Try it for yourself!

Using the principles shared here and the sample prompt below, you can feel confident about sending your students on a virtual field trip right in the middle of your classroom.

Sample virtual field trip prompt

Note: This prompt is effective in various liberal arts disciplines such as art, anthropology, history, art history, political science, and sociology.

- Provide students with a list of keywords related to a recent lecture or reading.

- From the JSTOR homepage, have students choose one word from the provided list to enter in the search bar–but, be sure to search by “image.”

Have students browse through the images from their search results. Students should choose five images that are most intriguing to them—for any reason at all—and save them to their personal Workspace by hovering over the image thumbnail and clicking on the ribbon in the lower right-hand corner. Students will need to register for a free personal account to access their Workspace, but this takes just a few minutes to set up.Tell students not to click to enlarge each image just yet; instruct them to save images to their Workspace without opening them. - After saving five images to their Workspace, students should move to their Workspace to open each individual image. As they do so, they should read the information provided with each image to learn more about it. Ask them: Which image or two speaks to you most and why? Jot down your thoughts on your laptop or a piece of paper.

- Next, direct students to get into groups of two or three. Groups can be arranged organically or by the instructor. Ask the students to share their images and any thoughts they have about them with their group members. Students should be directed to ask one another:

- Why did you first choose the five images at face value?

- What stuck out to you about them?

- Why did you choose the one or two images after viewing them more closely and reading about them?

- Most importantly, what connection—no matter how small—does the image or its context have to the recent lecture or reading, beyond the fact that it stemmed from a provided keyword list?

- Now, open the discussion up to the entire class. Call on one or two students from each small group and ask them to share not their own decision-making and thoughts, but rather those of their group members. This will prompt students to engage more deeply with the opinions and reflections of their peers.

- After tying the lesson together by noting how a handful of the images relate to the recent lecture or reading, provide students with a short reflection essay assignment that asks students to further articulate their chosen images and its connection to the lecture or reading. This essay can be completed in class, or assigned as homework, depending on time constraints and instructor preference. Provide specific essay instructions and citation directions to ensure students properly cite their sources.

You can download a PDF of the lesson plan above here.

Tell us how it went

We’d love to hear how incorporating Artstor on JSTOR into your teaching went. Complete this brief survey to provide feedback and share your experience!

Related content

Learning to Look series

By Virginia Seymour

Published by JSTOR Daily

Visual Literacy

By Edmund B. Feldman

Journal of Aesthetic Education, Vol. 10, No. 3/4, Bicentennial Issue (July–Oct., 1976), pp. 195-200

Published by University of Illinois Press

Digital Image Databases: A Study from the Undergraduate Point of View

By Teresa Slobuski

Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Fall, 2011), pp. 49-55

Published by The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Art Libraries Society of North America

About the author

Rumika Suzuki Hillyer is a Content & Community Engagement Manager at ITHAKA, where she leverages her teaching background and social media skills to connect with a diverse range of JSTOR users. From enrolling in an ESL program at a community college to earning a doctoral degree in sociology, Rumika has developed a comprehensive understanding of various tiers of higher education in the U.S. and their associated challenges. She is excited to embark on her new journey with ITHAKA, where she hopes to contribute to its mission and promote accessible and equitable higher education for all.