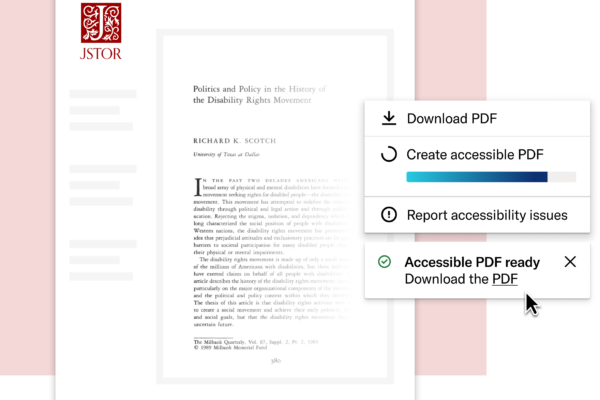

This blog post is part of a series dedicated to celebrating JSTOR’s 30th anniversary. Explore the whole series.

At JSTOR, our commitment to equal access to education is not a mere slogan. As a nonprofit organization in higher education, we understand that, in order to provide equitable access to higher education, you also must think about learners outside traditional academic institutions and build connections with them.

This is why we have the JSTOR Access in Prison initiative which enables learners inside jails and prisons to access the scholarly journals, books, and primary sources hosted on JSTOR.

This initiative first took its shape in 2007 as a single installation of the offline index (a searchable index of X articles used by incarcerated people to find and request articles) at the Bard Prison Initiative. Since 2019, supported by grants from the Mellon Foundation and the Ascendium Education Group, JSTOR has improved the offline index and developed an online version that meets strict prison security requirements. Today, more than a million learners have access to JSTOR in more than 1,400 prisons and jails around the world.

While we’ve highlighted JSTOR Access in Prison’s milestones and impact, fewer people know the full story: How did this initiative grow into such an integral part of JSTOR’s work?

To find out, I spoke with Stacy Burnett, Senior Manager of JSTOR Access in Prison.

Q: “Can you share a brief history of how JSTOR Access in Prison began?”

Stacy: The seeds of the JSTOR Access in Prison (JAIP hereafter) were planted in 2007, when the Bard Prison Initiative approached JSTOR with a question: could we help support their college-in-prison programming? At the time, the infrastructure didn’t exist, and the scale was modest – a few students, but we listened. Students in that early pilot used an index of the most cited articles on JSTOR and someone on the main campus would look up the student’s requests, print the articles, and bring them to the student inside the prison. When the reinstatement of Pell Grants for incarcerated students became likely, JSTOR’s leadership asked a pivotal question: How can anyone receive a quality education without access to an academic library? That question became the foundation for JAIP.

“I was reading your blog bio and saw that you took your first-ever college class through the Bard Prison Initiative and later earned an MBA in Sustainability from Bard Graduate Center after you came home. I hadn’t realized you had such a deep connection to JAIP even before joining ITHAKA! Could you share a bit more about your educational and professional journey?”

Stacy: The funniest thing is that I was solidly Team Public Health – while at BPI (Bard Prison Initiative), I took classes in that concentration, and not long after my release, NYC was pounded by the pandemic. BPI had prepared me for this, and I was incredibly proud to have the education that met that moment. I had the skills to keep myself and my neighbors safe. I was working toward an MPH, but while working in the Situation Room to manage outbreaks in NYC public schools, I worked with MBAs and realized I could actually do more to benefit my community with that education. COVID was happening, and I was in graduate school, and people kept sending me the ITHAKA job posting for someone to lead JSTOR Access in Prison.

I kind of had my hands full at the moment, but while I was in prison, I spent every spare moment in the BPI computer lab, researching Oscar Wilde, for no reason other than I stumbled across him while completing an assignment and I was fascinated. My classmates had dubbed me the JSTOR Queen, and they all thought of me when seeing that job posting. I responded, mostly because I wanted to thank the people who made this cool thing that kept me out of trouble while I was in prison, and let me think of myself as a scholar, an expert in something, and where I found respite from the strain of daily life in prison.

I was shocked to hear back from my now-boss, and the deeper I became in the interview process, and got to know the organization and the people working here, I thought this whole shindig was something really special. I wanted everyone to experience that joy that I had, pouring through the archives and discovering new things about the world and themselves in the process. I still have an entire rainforest worth of paper BPI staff had printed out for me about Oscar while I was in prison. I can go into the archives at any time now—I don’t really need to keep it—but sometimes I pull them out since it grounds me and reignites my passion for the work we do in the lab here.

Q: “What JAIP achievement are you most proud of?”

Stacy: It was almost unimaginable that the JSTOR archive could be accessible in jails and prisons. They’re murky environments, with wildly different tech capabilities available to people living inside those spaces. There were more questions and conundrums than answers and solutions, but several design jams, focus groups, and research projects later, we built a platform that could meet the needs of learners who are incarcerated, librarians, educators, and departments of corrections.

Q: “Is there anything you wish more JAIP supporters would understand?”

Stacy: While many focus on the numbers, our proudest accomplishments are quieter. They are the moments when someone in prison rediscovers their curiosity through the archives. When they begin to see the world differently. When they realize that knowledge is still within reach—and that they are still human, and we can see them. We are proud that JSTOR found an ethical way to support education in prison. We proved that the democratization of knowledge doesn’t have to stop at the prison gate. And we’re proud that when people leave prison, they carry more than the weight of incarceration—they carry new tools, a stronger internal compass, and the knowledge that JSTOR is waiting for them on the outside, too.

Q: “What has been JAIP’s biggest milestone to date?”

Stacy: In 2024, we reached a major milestone when JSTOR became available in over 1,000 correctional facilities worldwide. This achievement was not the result of a single breakthrough, but of years of relationship-building, ethical decision-making, and a commitment to our mission.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated digital infrastructure development in many facilities, making it possible to scale access more rapidly. But the real engine behind this growth was our community—educators, advocates, departments of corrections and, of course, incarcerated learners—who helped shape the initiative every step of the way.

Q: “What is your vision for the future of JSTOR Access in Prison?”

Stacy: Our vision for the future is simple. JSTOR Access in Prison should be as common as a general prison library. Expanding our offerings to include resources on digital, media, and information literacy, and supporting those reintegrating into society with tools for navigating the digital world are high on our priority list. We also see potential in building new solutions—perhaps a law library, or a searchable reentry resource to help people find the non-academic information they need to rebuild their lives.

JAIP is an example of what happens when an organization approaches a challenge with an open mind, an open heart, and has a strong commitment to its mission. It’s a testament to what’s possible when we listen, when we care, and when we believe that access to knowledge is truly for everyone. 18 years later, and we are still listening.

Interested in hearing more updates and achievements from JSTOR Access in Prison? Check out an inaugural post of the new series, Inside & Connected, to learn and understand more about JAIP’s work with institutions and people who use JSTOR while incarcerated. Stay tuned for more posts to come.

You can also receive JAIP’s news and updates directly to your inbox by signing up for quarterly newsletters, the Catalyst, from here.